Left Holding the Baby

In February 1850 Henry Cooper, surgeon and general practitioner of Ixworth, entered the Police Court at Worship Street, Shoreditch. He was not charged with any offence, nor was he involved in litigation, he was simply seeking the advice of a magistrate regarding the unusual position in which he found himself.

A month previously Dr Cooper had been travelling by rail, from Bury St Edmunds to London, with his friend Captain Lloyd. At Marks Tey an elegantly-dressed lady had entered their carriage carrying a baby; she had been sitting alone in first-class when she had felt unwell and so wished to be seated with other passengers as a precaution. Dr Cooper offered to assist the lady but she thought her illness was due simply to the fatigue of travelling and she soon seemed to feel better. When the train terminated at Shoreditch Dr Cooper again offered his assistance but the lady explained that her carriage and servant should be waiting there for her, however, would he mind looking after her baby and a small trunk while she went to check? Once an hour had passed without the lady returning I think Henry Cooper had probably realised that he was never going to see her again.

Eventually Henry continued into town with the child, a girl of about two months of age, and went to the home of a friend of his. When they undressed the baby they found a letter hidden in her clothing which stated that the child was of good parentage and that these parents fully intended to fund her future; money would be sent in response to advertisements placed in the national press. The parents would reclaim the child in due course. As evidence of their good intent the letter had two £10 notes enclosed with it. The child had remained at his friend’s house ever since.

Henry now had a dilemma. He had another friend in Suffolk who wanted to adopt the baby and Henry was keen to invest the £20 for the child’s benefit so as not to appear to have a mercenary motive, however, he had also been approached by ‘some gentleman in Devonshire.’ Through adverts in the Times he had met with this gentleman who claimed to be acting on behalf of the child’s mother and demanded the return of both child and property under threat of prosecution – no proof of his authority had been forthcoming.

SHOREDITCH – “A Looker-on in this Parish” is requested to COMMUNICATE FURTHER PARTICULARS, and he may fully rely on his information being immediately and strictly acted upon. A personal interview would be desirable as the means of arriving at a safe and quick elucidation of the affair, when the closest secrecy would be observed. The Times, Wednesday 30 January, 1850.

Henry was looking for a course of action which would free him of his unwanted responsibility while best serving the child’s interests. He expressed the opinion that the lady, in her early 30s, had been married and of reasonable means; the child had been wrapped in a silk cloak lined with ermine and the trunk was full of expensive clothing for a young girl. The magistrate doubted that he could satisfy Henry’s desire and simply suggested that the child should be handed over to the Officers of Shoreditch Parish. There was some chance that they might identify the mother but a future in the workhouse was far more likely. As the Times reporter who covered the case wrote in conclusion: ‘the applicant thanked the Magistrate for his advice and quitted the court, but it was pretty manifest from his manner that he was disinclined to adopt the suggestion thrown out by the Bench.’

What became of the little girl is not known but she probably did not go to the workhouse. The press coverage was limited to the original incident and that one court appearance; however, the court proceedings also appeared in Punch magazine in the form of a 24-verse poem written by none other than William Makepeace Thackeray. The poem is included in his collected works as ‘The Lamentable Ballad of the Foundling of Shoreditch’. Cooper family tradition has it that Henry and Thackeray were friends.

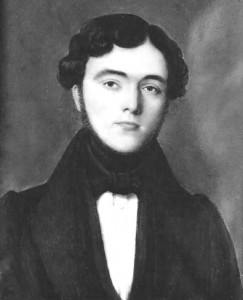

Henry Cooper and Ixworth

Henry Ralph Cooper was a Shropshire lad and came to Ixworth in 1841 in reply to an advertisement in the Lancet. Thomas Barsham, surgeon, of Norton, was looking for an assistant to cover the Ixworth area. The pay was £100 per year, a house was included and there was the prospect of a partnership in due course. One stipulation was that the new assistant was under a bond not to set up in business in competition with his boss. All was well at first and they operated from the ‘Apothecary‘s Shop’ which bore a brass plaque with Barsham & Cooper on it. (This was probably 27 High Street where Henry lived throughout his time in Ixworth.) Unfortunately they fell out in 1845, Thomas accused Henry of setting up in opposition to him and then Henry, bewilderingly, sued Thomas for four years’ wages.

Despite the pair settling out of court Henry set out on a protracted series of court cases against Thomas, each leading him further into debt due to legal fees. The matter at issue was payment for the upkeep of a horse for the business – about £40 in all. Their dispute was acrimonious; Henry was bound over to keep the peace for threatening to horsewhip Thomas at one point.

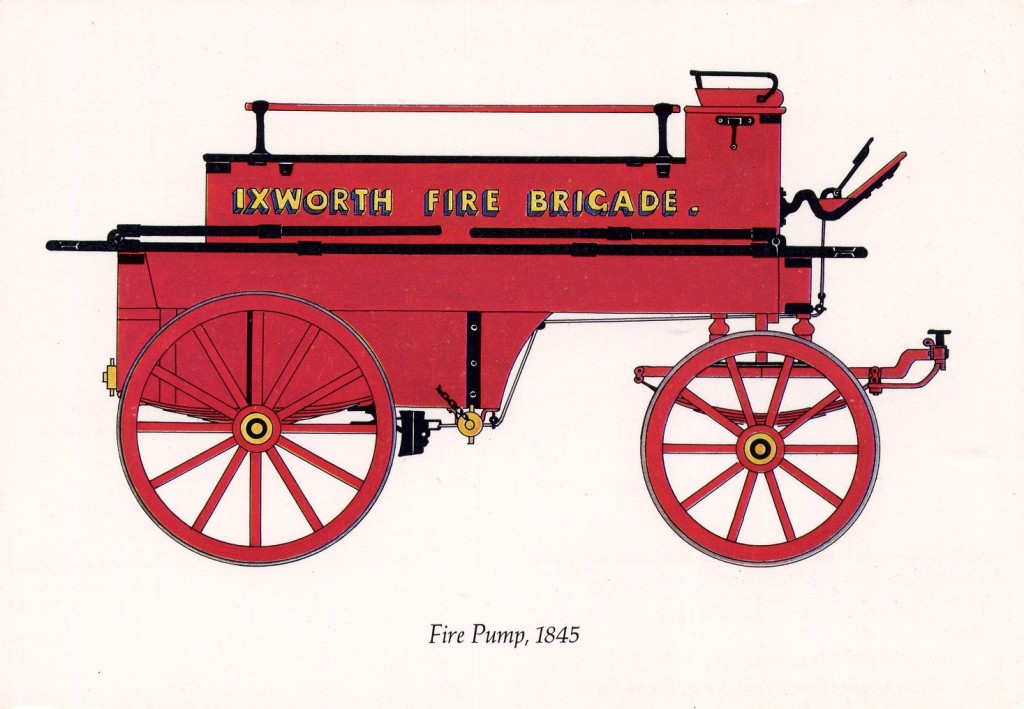

Henry had made his mark in his early years in Ixworth through the Fire Brigade. In the early 1840s there was a trend to ‘incendiarism’ in West Suffolk – people were setting fire to haystacks and remote properties. He organised a subscription and raised enough money for the village to buy a state-of-the-art fire engine. Built by Merryweather of London it was light-weight and could discharge 80 gallons of water per minute up to a height of 100 feet; it is still part of the collection at the Museum of East Anglian Life in Stowmarket. In November 1845 a thrilling account appeared in the Bury & Norwich Post in which Henry discovered a fire on a farm at Stanton late one night, rode quickly to Ixworth, brought the fire engine and commanded the Brigade as they extinguished the flames. It is likely that Henry submitted this report to the paper himself and later letters pointed out that two other fire engines were also in attendance that night and that the fire was nearly out before any of them got there. Henry was always a man to make sure that all knew of his qualities and achievements.

He also saw himself as a champion of the poor and ignorant against the rich and the judiciary. Whether because it had always been his inclination, or because the cases against Thomas Barsham had been so thrilling, Henry used the courts as his tool in his fight against injustice. He had a deep suspicion of anyone in public office and brought charges against two successive Chief Constables, one for dealing with poachers and the next for permitting fraud among police officers. His campaigning zeal is perhaps best illustrated by the case of the Ixworth Thorpe Town Estate Trust.

The Trust was a charity which was meant to use the income from a piece of land to assist the poor. Henry had been told by the people of Ixworth Thorpe that the Trust was being mismanaged and they had received no income from it for years. Henry wrote to the Charities Commission demanding an inquiry; the inquiry found no fault with the Trust. Four years later, at Henry’s suggestion, eleven men of the village felled a grove of trees belonging to the Trust in an effort to bring their grievances before the court; the men risked lengthy prison sentences for doing so. In court Henry presented himself as the men’s attorney but was told he was not qualified so they had to hire a solicitor. Henry then persuaded the men to plead not guilty and take the case to a higher court. At the next hearing another solicitor had been hired and he advised them to plead guilty and throw themselves on the mercy of the court in the hope of only being fined. The prosecution agreed to this outcome and both prosecution and defence attorneys had some very harsh words for the irresponsible actions of Henry Cooper.

The Bury & Norwich Post carries reports on at least sixty court cases and tribunals involving Henry: he charged people with assault and was himself charged with the same; he prosecuted a man for cruelty to a horse in the High Street; he encouraged a girl to bring a doubtful case for indecent assault and then interfered in her resulting perjury trial; he had several attempts to charge a man with operating a steam threshing machine too close to the highway and scaring his pony. He often represented himself in court and was less than expert at it: he used the wrong acts of parliament, forgot to bring witnesses or evidence along and rarely anticipated the opposition solicitor’s defence. The cost of his hobby just kept on rising. His final action against Thomas Barsham had cost him £212 and as a result he was taken into Bury Gaol as a debtor, from where he escaped and went on the run for a month.

In later years Henry found another outlet in writing anonymous letters to the Bury & Norwich Post. He would use pseudonyms such as A Ratepayer, Amor Justitiae, Quietus, Ignoramus and Perfectly Astonished of Ixworth. He had several key subjects on which to write: the use of the Game Laws to oppress the poor, the inconsistency of judgements by the Ixworth Magistrates, the poor performance of the Ixworth Police, rowdy behaviour in Ixworth High Street on a Sunday and, of course, the use of steam engines on the highway. Whenever Henry was involved in an unsuccessful court case it was normal for a letter about it to appear the following week.

“Then – and it will hardly be credited – there is a certain description of house by the Parsonage, close to the church, and within a few doors of the police-station, with three inmates of the lowest caste, but neither the parish authorities nor the police have taken any steps to remove this very great nuisance.”

Letter to the editor of the Bury & Norwich Post from AMOR JUSTITIAE, re Ixworth Sessions Justice

6 October 1857

“As soon as that blest morn appears, so soon begins the row: the old, the young, and middle-aged are seen congregating at their usual rendezvous, and then commences their laughing, shrieking, shouting, swearing, singing, whistling, hooting – all this at intervals during the day, with the addition, by way of variety, of the most obscene expressions, disgusting remarks, and insulting epithets to passers-by: and if such venture to expostulate or reprove, they are saluted with the most fiend-like yells of derision , from perhaps twenty or thirty of this depraved rabble in one place, ten or fifteen in another, and more or less in another, for we are favoured with three or four of these precious haunts, where the worst blackguardism is to be heard.”

Letter to the editor of the Bury & Norwich Post from QUIETUS, re Ixworth on Sunday

12 January 1858

[Particular reference is made to the ‘Greyhound Corner.’]

Henry’s wife, Eliza, had died in 1847 leaving him with three young children but his life seemed to be settling down a little when he remarried, to Frances Brooks of Lincolnshire, in 1862. She bore him a son in 1863, however, things were about to go horribly wrong. In August 1863 Henry embarked on a series of cases against the Thingoe Union; he claimed to have been attending to the medical needs of paupers but not getting paid. In fact the actions seem to have had more to do with his dislike of the Union’s doctor, Mr Taylor. He had his usual lack of success and his debts continued to rise.

Also in August Henry was attending court in Liverpool charged with libel. He had an uncle called Captain Baddeley and either they were very close or Henry had expectations because Henry’s first son was named Baddeley in his honour. Captain Baddeley had died and left his entire estate to a clergyman with whom he lived (the clergyman was the Reverend Padley, one can imagine what a modern headline writer would have made of that). Henry and five other nephews petitioned the Coroner and Police to exhume his uncle’s body so that the cause of death could be verified. When refused they took their case to the Secretary of State. They were clearly disappointed at being disinherited but it still seems a bit of an extreme measure just to get a share of only £500. Henry had given some ill-judged comments to the local newspapers regarding a suspicion of poisoning in the case and hence the trial. He admitted libel with resulting damages and costs totalling £497; the Sheriff of Suffolk ordered his household possessions to be sold to raise the sum. Within a month he was back in court unsuccessfully suing the Thingoe Union again.

December saw him declared bankrupt with debts of just over £1280. In March 1864 Henry’s youngest daughter, Elizabeth, died aged 21 and two months later he followed her to the grave due to kidney failure, he was 49 years old. The Cooper men have a history of heart problems and Henry’s death might have been a result of a stress-induced condition. Henry, Eliza and Elizabeth are buried together, close to the west door of the tower of St Mary’s Church. His new wife returned to Lincolnshire in the early stages of a pregnancy which would lead to the birth of a daughter in December 1864.

In March 1866, 27 High Street was sold by auction, following a decree of the Court of Chancery, to raise money for Henry’s dependants. The sitting tenant at that point was Henry Taylor Esq, surgeon; Henry’s arch enemy.

[Postscript: Henry’s first son, Charles Baddeley Cooper, remained in Ixworth for a while and was himself in court in September 1867. He was accusing one of his father’s creditors of assaulting him in the High Street but the case was not proven. Something of a chip off the old block it would seem. As a matter of interest, Charles had moved his whole family to Toronto by 1881.]

I owe a great debt of gratitude to Edward Waterson, Henry’s great-great-grandson, for allowing me to use Henry’s image and for supplying some Cooper family history to fill the gaps in my narrative.

You can down the full article by clicking here – This article was written by Steve Wilson and contributed by Mike Dean – they hope that it is of interest as you wander the village and wonder at what happened in Ixworth centuries ago.